- Home

- /

- Product Management

- /

- The Veblen Effect: How Sky-High…

Introduction

In a world where new gadgets launch with fanfare that rivals blockbuster movies, few products stir up as much excitement as Apple’s latest iPhone. As rumors swirl about the iPhone 17, set to hit shelves with features like advanced AI integration and sleeker designs, lines form outside stores and pre-orders sell out in minutes. But why do people flock to a device that costs more than many laptops, especially when cheaper alternatives perform just as well? This behavior ties into a fascinating economic concept known as the Veblen effect. In this article, we’ll explore what the Veblen effect means, its origins, and how it explains the ongoing obsession with premium smartphones like the iPhone 17. We’ll dive into the psychology behind it, real-world examples, and even some critiques to give you a full picture.

Check out Apple Event 2025 highlights here.

What Is the Veblen Effect?

At its core, the Veblen effect describes a situation where the demand for a product rises as its price increases. This runs counter to basic economic principles, where higher prices typically lead to lower demand. Named after economist Thorstein Veblen, who introduced the idea in his 1899 book “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” it highlights how certain goods become more desirable precisely because they are expensive.

Veblen argued that in affluent societies, people use high-priced items to signal their wealth and social status. These aren’t just any products; they are “Veblen goods,” like luxury watches, designer handbags, or exclusive art pieces. For these items, a steep price tag isn’t a barrier; it’s the main attraction. It tells the world, “I can afford this, and that sets me apart.”

To understand this better, think about supply and demand curves. In standard economics, as prices go up, fewer people buy. But with Veblen goods, the curve bends upward at higher prices because exclusivity drives appeal. This effect is most pronounced in markets where status matters more than utility.

The Historical Roots of the Veblen Effect

Thorstein Veblen, a Norwegian-American economist born in 1857, wasn’t your typical academic. He grew up on a farm in Wisconsin and brought a sharp, satirical eye to his studies of American society. In “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” Veblen critiqued the upper class for their “conspicuous consumption,” a term he coined to describe spending money on unnecessary luxuries to show off.

Veblen’s ideas drew from observations of the Gilded Age, a time of rapid industrialisation and wealth inequality in the late 19th century. He saw how the rich bought extravagant items not for practical use but to display their position. This wasn’t limited to goods; it extended to leisure activities and even wasteful habits, like hosting lavish parties.

Over time, economists have built on Veblen’s work. In the 20th century, figures like John Kenneth Galbraith explored similar themes in books like “The Affluent Society,” linking consumerism to social dynamics. Today, the Veblen effect is taught in economics courses worldwide, often alongside concepts like the Giffen paradox, where demand rises with price due to necessity rather than status.

How the Veblen Effect Plays Out in Today’s Markets

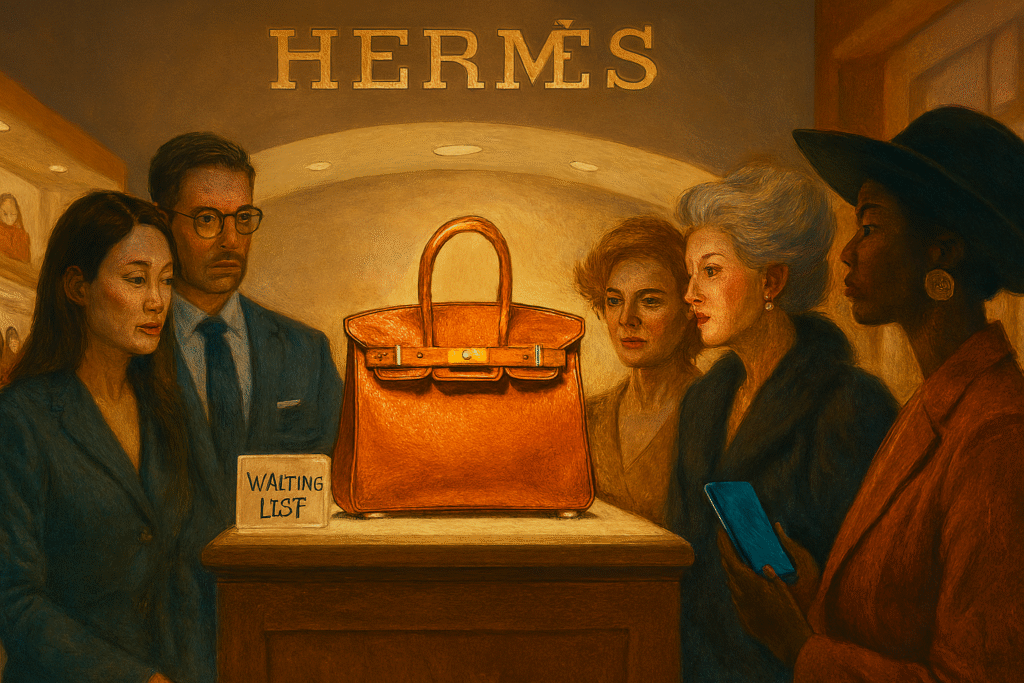

In modern economies, the Veblen effect thrives in luxury sectors. Take high-end fashion: A Hermès Birkin bag can cost tens of thousands of dollars, yet waiting lists stretch for years. The price doesn’t deter buyers; it enhances the bag’s allure as a symbol of elite access.

Wine and art markets show this too. A bottle of rare vintage might fetch millions at auction, not just for taste but for the prestige of ownership. Even in tech, limited-edition gadgets or custom-built supercars follow the pattern. Companies like Rolex or Ferrari deliberately keep production low and prices high to maintain that exclusive vibe.

But it’s not all about pure luxury. Sometimes, everyday items can exhibit Veblen traits if marketed right. Organic foods or eco-friendly products often command premiums, partly because they signal a certain lifestyle or values. The key is perception: When a product becomes a status marker, price becomes a feature, not a flaw.

The iPhone Phenomenon: A Modern Veblen Good?

Apple’s iPhone has evolved from a revolutionary phone in 2007 to a cultural icon. Each new model promises cutting-edge tech, from better cameras to faster processors, but the real draw is the brand itself. Owning the latest iPhone says something about you: You’re tech-savvy, successful, and in tune with trends.

This status element aligns perfectly with the Veblen effect. Base models start around $800, with pro versions pushing past $1,000, yet sales soar. In 2024, Apple reported record revenues from iPhone sales, even as competitors like Samsung offered comparable features at lower prices. Why? Because the iPhone isn’t just a phone; it’s a badge of belonging to a premium ecosystem.

Features like seamless integration with other Apple devices add value, but the hype around launches amplifies the effect. Social media buzz, celebrity endorsements, and viral unboxing videos turn buying an iPhone into a shared experience. For many, it’s worth the cost to avoid feeling left out.

Connecting the Veblen Effect to the iPhone 17 Craze

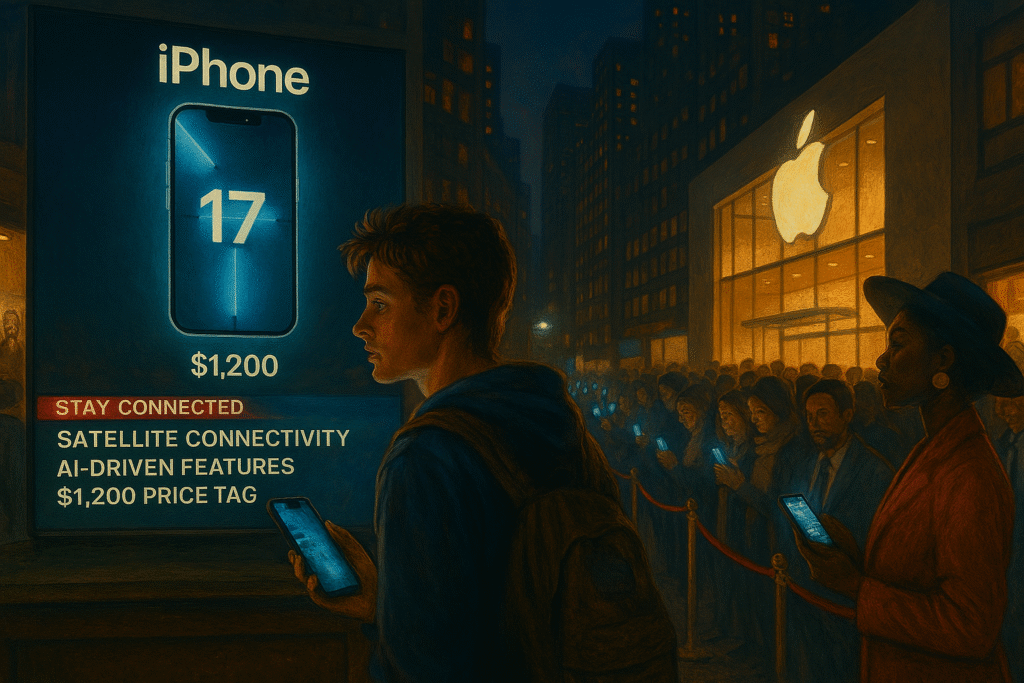

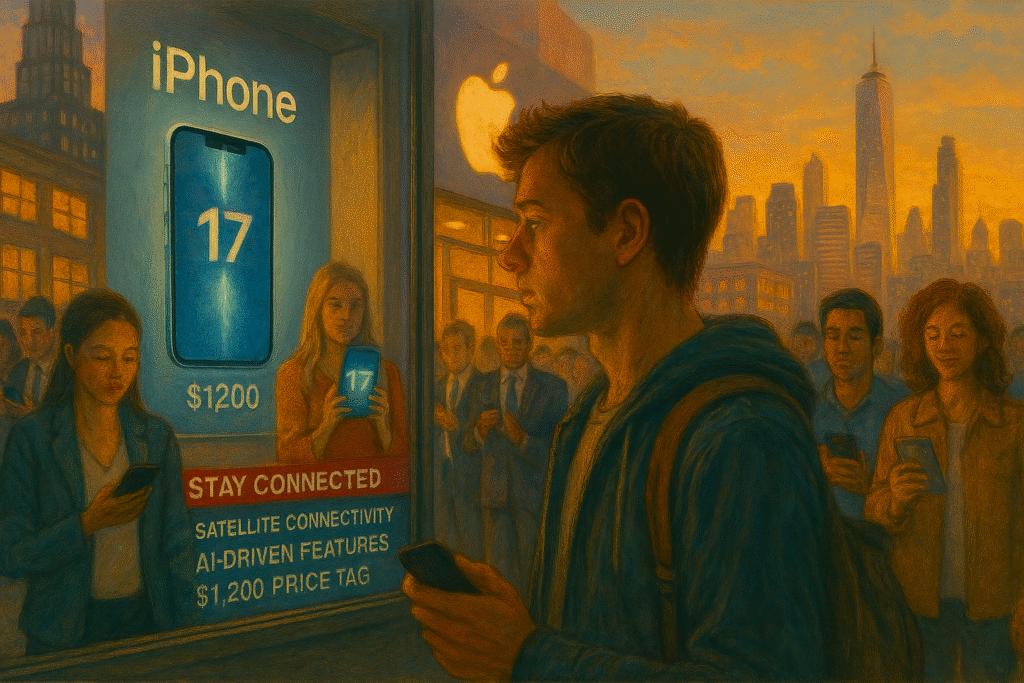

Now, let’s tie this to the iPhone 17. As of late 2025, speculation is rampant about its rumoured upgrades: A slimmer profile, under-display cameras for a seamless screen, enhanced AI for personalised experiences, and perhaps even satellite connectivity for remote areas. These innovations sound impressive, but the real frenzy stems from the Veblen dynamic.

Apple prices its flagships high, often increasing costs with each generation to signal superiority. The iPhone 17 Pro Max could top $1,200, yet demand is expected to spike. Fans camp out or pay scalpers double to get one first, not for the tech alone, but for the prestige of being an early adopter.

This craze defies logic in a saturated market. Android phones from Google or OnePlus match or exceed iPhone specs at half the price, with longer battery life or customisable software. But Apple’s marketing masterstroke positions the iPhone as aspirational. It’s about joining an exclusive club, where the high price filters out the masses and reinforces status.

Social proof plays a role, too. When influencers and executives flash the newest model, it creates a ripple effect. In professional settings, pulling out an older phone might subtly signal lower status, pushing people to upgrade prematurely.

The Psychology and Social Drivers Behind It

Digging deeper, the Veblen effect taps into human psychology. Social comparison theory, developed by psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1950s, explains how we evaluate ourselves against others. In consumer culture, this means using possessions to climb social ladders.

FOMO, or fear of missing out, amplifies this. With iPhone launches, limited stock creates urgency, making the purchase feel like a win. Behavioral economists like Daniel Kahneman have shown how emotions override rational choices, leading to “irrational exuberance” in buying.

Culturally, this varies. In emerging markets like India or Brazil, owning an iPhone signals upward mobility. In the U.S., it’s more about trendsetting. Apple leverages this with ecosystem lock-in: Once you’re in with apps, services, and accessories, switching feels costly.

Criticisms and Limits of the Veblen Effect

Not everyone buys into the Veblen effect as a universal rule. Critics argue it’s hard to isolate from other factors, like quality improvements or brand loyalty. For instance, iPhones do offer superior privacy and longevity, which justifies a premium.

There’s also a ceiling: If prices get too high, even status seekers might balk. Economic downturns can shift priorities to value over prestige, as seen during recessions when luxury sales dip.

Ethically, some view conspicuous consumption as wasteful, contributing to inequality and environmental strain. Producing high-end gadgets requires rare materials, raising questions about sustainability.

Recommended Readings

- “The Theory of the Leisure Class” by Thorstein Veblen: The foundational text that introduces conspicuous consumption and the ideas behind the Veblen effect.

- “The Affluent Society” by John Kenneth Galbraith: Explores consumerism in modern economies and builds on Veblen’s critiques.

- “Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman: Delves into the psychological biases that drive irrational economic decisions, including status-driven purchases.

- “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion” by Robert Cialdini: Covers social proof and other principles that explain why we follow trends in buying luxury goods.

- “Status Anxiety” by Alain de Botton: Examines the social pressures behind seeking prestige through possessions.

FAQ

Q1: What exactly is a Veblen good?

A: A Veblen good is a product whose demand increases with its price because it’s seen as a status symbol. Examples include luxury cars, fine jewelry, and high-end tech like certain smartphones.

Q2: Does the Veblen effect apply to all luxury items?

A: Not necessarily. It works best for items where status is key, but factors like quality or scarcity can influence it. Not every expensive product qualifies if demand drops with price hikes.

Q3: Why does the iPhone 17 fit the Veblen effect?

A: Its high price enhances its appeal as a premium, exclusive device. People buy it to signal success and stay ahead of trends, even with cheaper alternatives available.

Q4: Can the Veblen effect ever reverse?

A: Yes, if a product becomes too common or loses its elite image, demand might normalize. Economic changes or shifts in consumer values can also weaken it.

Q5: Is the Veblen effect the same as conspicuous consumption?

A: They’re related but not identical. Conspicuous consumption is the act of buying to show off, while the Veblen effect specifically ties that to rising demand with higher prices.

Conclusion

The Veblen effect sheds light on why we chase expensive items like the iPhone 17, even when logic suggests otherwise. It’s a blend of economics, psychology, and culture that turns price into a magnet for desire. As technology advances, this phenomenon will likely persist, with brands like Apple continuing to capitalise on our need for status. But it’s worth pausing to ask: Do we buy for the features or the feeling? Understanding Veblen can help us make smarter choices in a world of endless upgrades.

Leave a Reply